05-05-2023, 02:57 PM

A couple of times recently people have pointed out the (sub?)cultural aspects of gun violence. A couple of days ago I listened to an NPR segment that addresses it (just under 6 minutes long):

https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2023/05/...onal-rates

The segment refers to a study done by the Nationhood Lab:

https://www.nationhoodlab.org/about-the-nationhood-lab/

[snippets - it's a very long article]

https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2023/05/...onal-rates

The segment refers to a study done by the Nationhood Lab:

https://www.nationhoodlab.org/about-the-nationhood-lab/

[snippets - it's a very long article]

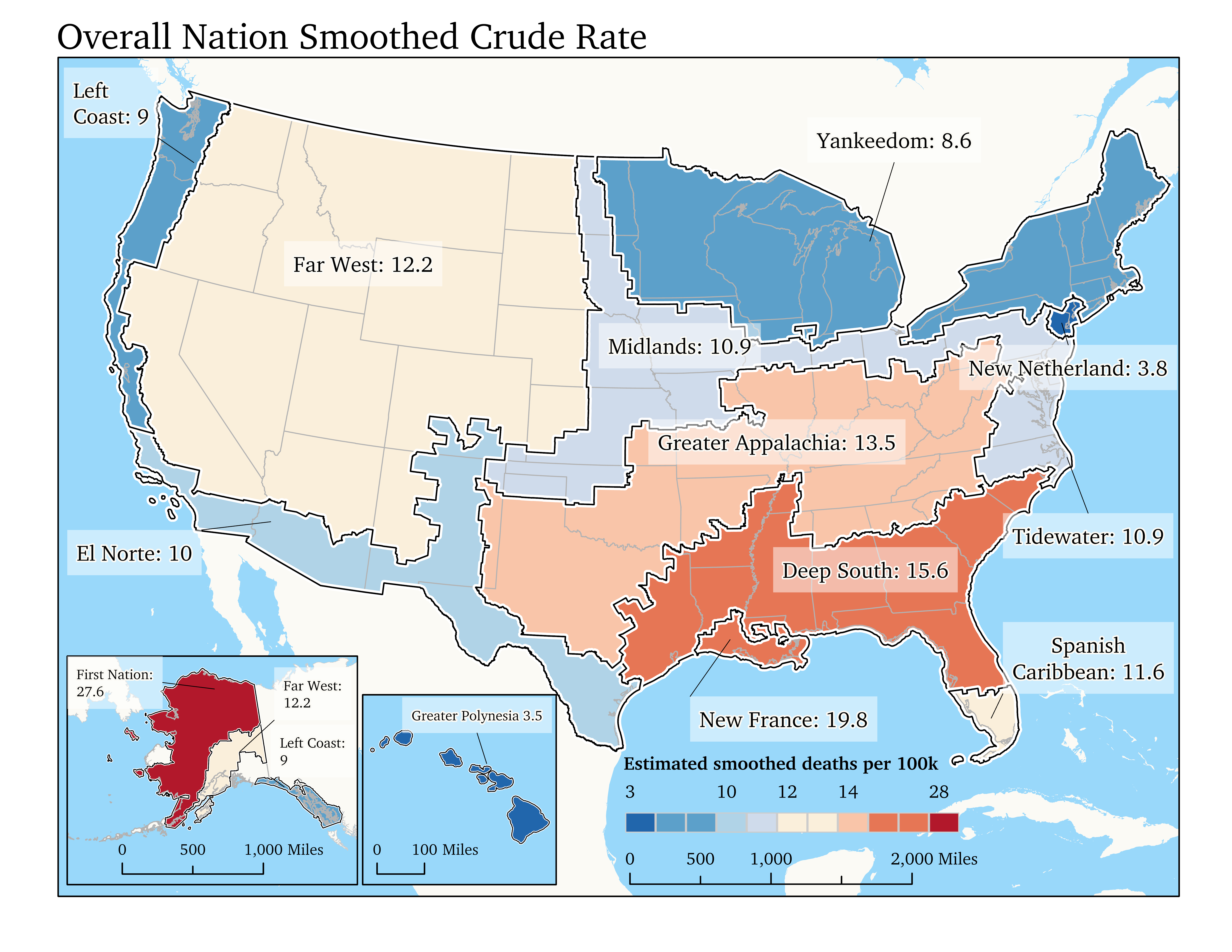

There are a lot of graphics - here is a general one:

But what’s less well appreciated is how much the incidence of deadly violence generally – and gun violence in particular – varies by region. It’s as if we live in separate countries, some of which have gun violence profiles that look like Canada’s, others that resemble the Philippines, Panama, or Peru. And the reasons for this go back centuries, part and parcel of dominant cultural heritages laid down by the rival colonial projects that spread across our continent in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. Reducing levels of deadly violence in the U.S. won’t be easy, but understanding the nature of the problem is an essential first step.

- - -

In a classic 1993 study the social psychologist Richard Nisbett of the University of Michigan, noted that regions initially “settled by sober Puritans, Quakers and Dutch farmer-artisans”—that is, Yankeedom, the Midlands and New Netherland—were organized around a yeoman agricultural economy that rewarded “quiet, cooperative citizenship, with each individual being capable of uniting for the common good.” The South—and by this he meant the nations I call Tidewater and Deep South—was settled by “swashbuckling Cavaliers of noble or landed gentry status, who took their values . . . from the knightly, medieval standards of manly honor and virtue.”

- - -

These southern cultures developed what anthropologists call a “culture of honor tradition” in which males treasure their honor and believed it can be diminished if an insult, slight or wrong were ignored. “In these cultures you have to establish yourself as tough and not to be messed with and the way to do that to let people know you’re not to be messed with on big matters is to show them you are not to be messed with in small matters either,” says University of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign psychologist Dov Cohen, who has researched various aspects of the phenomenon with Nisbett and others.

- - -

In these same regions this aggressive proclivity is coupled with the violent legacy of having been slave societies. Before 1865, enslaved people were kept in check through the threat and application of violence including whippings, torture, and often gruesome executions. For nearly a century thereafter, similar measures were used by the KKK, off-duty law enforcement, and thousands of ordinary white citizens to enforce a racial caste system. The Monroe and Florence Works Today Project mapped every lynching and deadly race riot in the U.S. between 1848 and 1964 and found over 90 percent of the incidents occurred in those three regions or El Norte, where Deep Southern “Anglos” enforced a caste system on the region’s Hispanic majority. In places with a legacy of lynching — which is only now starting to pass out of living memory – SUNY-Albany sociologist Steven Messner and two colleagues found a significant increase one type of homicide, the argument-related killing of Blacks by whites, that isn’t explained by other factors.

By contrast, the Yankee and Midland cultural legacies featured factors that dampened deadly violence by individuals. The Puritan founders of Yankeedom promoted self-doubt and self-restraint, and their Unitarian and Congregational spiritual descendants believed vengeance would not receive the approval of an all-knowing God (though there were plenty of loopholes in regards to indigenous people and others regarded as being outside the community.) This region was the center of the 19th-century death penalty reform movement, which began eliminating capital punishment for burglary, robbery, sodomy and other nonlethal crimes, and today none of the states it controls permit executions save New Hampshire, which hasn’t killed a person since 1939. The Midlands were founded by pacifist Quakers and attracted likeminded emigrants who set the cultural tone: Mennonites, Amish, Moravians, German Lutheran pietists and others who believed violence in any form was unacceptable.